Are Figs Vegan? The Surprising Truth About the Fig Wasp

A science-based look at the fig's life cycle and why most vegans have no problem eating them.

Yes, figs are generally considered vegan.

The confusion stems from their unique pollination process involving fig wasps. A female wasp enters the fig, pollinates it, and dies inside.

But what matters is that you’re not eating insect parts.

The fig produces an enzyme called ficin that completely breaks down the wasp’s body into proteins, which the plant absorbs. [1]

Most commercially grown figs don’t even require wasps anymore. They’re varieties bred specifically for commercial production that can pollinate themselves. [2]

The rest of this guide explains the science behind fig pollination, addresses the ethical concerns, and helps you make an informed choice about including figs in your plant-based diet.

The Fig and the Wasp

The fig (Ficus carica) and the fig wasp share one of nature’s most intricate partnerships. This relationship, called mutualism = a biological interaction where both organisms benefit, has existed for millions of years. [3]

What makes figs different from other fruits is that they’re not technically a fruit at all. A fig is an inflorescence, a structure containing dozens of tiny flowers clustered inside. The fig’s flesh is actually inverted flower tissue. [4]

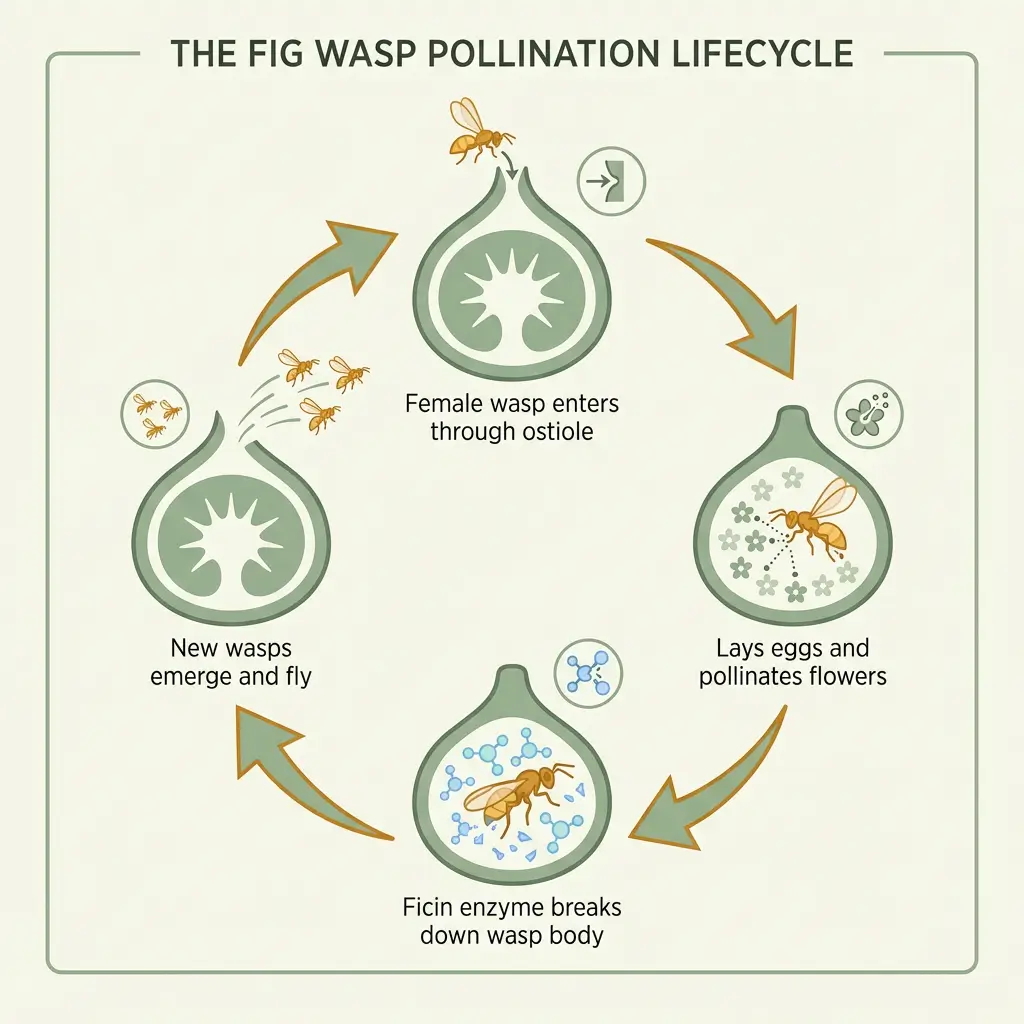

The pollination process works like this:

- A female fig wasp, smaller than a grain of rice, squeezes through a tiny opening called the ostiole to enter the fig. The opening is so narrow that she loses her wings and antennae during entry. She can never leave.

- Inside, she lays her eggs among the flowers and simultaneously pollinates them with pollen from her birth fig. The male flowers provide a nursery for her larvae. Once her eggs are laid, she dies inside the fig. [5]

- The baby wasps develop, mate inside the fig, and the females fly off to repeat the cycle. Males die inside, never seeing daylight.

(Ed. note: This process has evolved over tens of millions of years, making it one of the oldest pollination partnerships on Earth.)

What Really Happens to the Wasp Inside the Fig?

“Am I actually eating a dead wasp when I bite into a fig?”

No. The wasp’s body doesn’t remain intact inside the fig you eat.

Figs produce ficin, a proteolytic enzyme that breaks down proteins. When the wasp dies inside the fig, ficin goes to work. The enzyme dissolves the wasp’s exoskeleton, tissues, and proteins completely. The fig absorbs these broken-down proteins as nutrients, similar to how carnivorous plants digest insects. [6]

By the time a fig reaches your plate, no wasp parts remain. Zero legs, no wings, no intact body. The proteins from the wasp become indistinguishable from the fig’s own proteins at the molecular level.

What about that crunchy texture inside figs? Those are seeds, not insect remnants. Figs contain hundreds of tiny seeds that give them their characteristic texture.

Think of it this way: the wasp’s biological material becomes part of the fig’s structure. The distinction between “wasp” and “fig” ceases to exist at the molecular level. [7]

Does this process sound unsettling? Consider that plants absorb nutrients from decomposed animals in soil all the time. The fig just does it more directly.

Does the Wasp’s Death Violate Vegan Principles?

This question sits at the heart of the fig debate among vegans.

The Vegan Society defines veganism as “a philosophy and way of living which seeks to exclude, as far as is possible and practicable, all forms of exploitation of, and cruelty to, animals.” [8]

Most vegans accept figs because the wasp’s death occurs through a natural symbiotic process, not human exploitation. The relationship existed millions of years before humans cultivated figs. We didn’t create this system for our benefit.

Veganism focuses on reducing intentional harm and exploitation. Natural ecological processes, even those resulting in animal death, fall outside the scope of what vegans can practically avoid.

Consider these parallels to understand the distinction between intentional and incidental harm:

Combine harvesters kill field mice, rabbits, and insects during grain harvests. Farmers don’t harvest wheat TO kill mice. The deaths happen as an unavoidable consequence of growing food at scale. [9]

Pesticides (even organic ones) kill insects that threaten crops. Without pest control, crop yields would plummet, making plant-based diets less accessible.

Tilling soil destroys earthworm habitats and kills organisms living underground. Yet tilling remains standard practice in vegetable farming.

The key difference is that these deaths are incidental to plant agriculture, not its purpose. Nobody profits from the death itself. The same logic applies to figs. The wasp doesn’t die because humans want to exploit it. The wasp dies completing its natural reproductive cycle, which happens to benefit the fig tree.

“But doesn’t buying figs create demand for a system that kills wasps?”

Only for certain fig varieties, and even then, the wasp’s death serves the wasp’s own reproductive goals. The wasp enters the fig voluntarily to lay eggs, not because humans force the interaction. This distinguishes it from factory farming, where animals are bred specifically to be killed for human consumption.

Some vegans still choose to avoid figs based on personal ethics. That’s valid. Veganism allows room for individual interpretation on edge cases like this.

Choosing Figs Without Wasps

Not all figs require wasp pollination. This fact changes the entire discussion.

Fig varieties fall into two categories:

Common figs (can pollinate themselves): These develop fruit through parthenocarpy, which means the fig produces fruit without needing pollination or fertilization. Think of it as the fig equivalent of seedless grapes. No wasps needed, no wasps involved. [10]

Smyrna figs (need wasps): These require pollination from the Blastophaga wasp to produce fruit. Without the wasp, the figs drop from the tree before ripening. [11]

Common fig varieties you’ll find in stores:

- Black Mission (the most popular variety in North America)

- Brown Turkey (sweet, purple-brown skin)

- Celeste (small, sweet, cold hardy)

- Adriatic (light green skin, often used for dried figs)

- Kadota (thick skinned, used for preserves)

Smyrna varieties that need wasps:

- Calimyrna (large, golden, nutty flavor)

- Marabout

- Zidi

Keep in mind that roughly 90% of commercially grown figs in the United States are common figs that can pollinate themselves. [12]

Why does this matter?

Because it means the figs at your grocery store, farmers market, or in your dried fruit mix are almost certainly varieties that never involved wasps at all.

If you want absolute certainty, ask produce managers about the variety. Black Mission and Brown Turkey dominate commercial production because they’re reliable, productive, and don’t require the complex wasp pollination system.

So, Are Figs Vegan?

Should vegans eat figs? The answer depends on your personal ethical framework, but the science provides clear guidance.

Key points to remember:

The enzyme ficin completely breaks down any wasp that dies inside a fig. You’re not consuming insect parts.

The fig and wasp relationship is a natural mutualism that predates human cultivation. It’s not a system of exploitation we created or maintain.

Most commercial figs are varieties that can pollinate themselves and never involve wasps at all.

Avoiding figs doesn’t meaningfully reduce animal suffering compared to focusing on direct animal exploitation in food systems.

For the vast majority of vegans, eating figs aligns perfectly with their ethical principles. The process mirrors countless other natural cycles where organisms interact, reproduce, and die as part of ecosystem function.

“But what if I’m still uncomfortable with it?”

That’s your choice to make. Some vegans avoid figs, honey, and foods grown with animal-based fertilizers. Others draw the line at direct animal exploitation. Both approaches are valid expressions of vegan ethics.

The important thing is making an informed decision based on facts, not misconceptions about eating wasp carcasses.

Frequently Asked Questions About Figs and Veganism

.

References

- [1] Galil, J. and Eisikowitch, D. – “On the Pollination Ecology of Ficus sycomorus in East Africa” – Ecology, 1968

https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.2307/1934454 - [2] Vossen, P.M. and Silver, D. – “Growing temperate tree fruit and nut crops in the home garden” – University of California Cooperative Extension, 2000 (NOT 2007)

Note: This is a series of fact sheets, not a single publication - [3] Herre, E.A., Jandér, K.C., and Machado, C.A. – “Evolutionary ecology of figs and their associates: Recent progress and outstanding puzzles” – Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 2008 https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110232

- [4] Cruaud, A. et al. – “An extreme case of plant-insect codiversification: figs and fig-pollinating wasps” – Systematic Biology, 2012 https://academic.oup.com/sysbio/article/61/6/1029/1667297

- [5] Cook, J.M. and Rasplus, J.Y. – “Mutualists with attitude: coevolving fig wasps and figs” – Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2003 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169534703000624

- [6] Machado, C.A. et al. – “Phylogenetic relationships, historical biogeography and character evolution of fig-pollinating wasps” – Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 2001 https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2000.1418

- [7] Devaraj, K.B. et al. – “Purification, characterization, and solvent-induced thermal stabilization of ficin from Ficus carica” – Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2008

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18991449/ - [8] Flaishman, M.A., Rodov, V., and Stover, E. – “The Fig: Botany, Horticulture, and Breeding” – Horticultural Reviews, 2008

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9780470380147.ch2 - [9] The Vegan Society – “Definition of veganism” – 2024 https://www.vegansociety.com/go-vegan/definition-veganism

- [10] Fischer, B. and Lamey, A. – “Field Deaths in Plant Agriculture” – Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 2018

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10806-018-9733-8 - [11] Tew, T.E. and Macdonald, D.W. – “The effects of harvest on arable wood mice Apodemus sylvaticus” – Biological Conservation, 1993

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/000632079390060E - [12] Storey, W.B. – “Figs” – Chapter in: Janick, J. and Moore, J.N. (eds.) Advances in Fruit Breeding – Purdue University Press, 1975

- [13] Condit, I.J. – “Fig Varieties: A Monograph” – Hilgardia 23(11):323-538, University of California Agricultural Experiment Station, 1955

https://fruitsandnuts.ucdavis.edu/sites/g/files/dgvnsk12441/files/391-296.pdf - [14] USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service – “Noncitrus Fruits and Nuts – 2023 Summary” – May 2024

https://esmis.nal.usda.gov/sites/default/release-files/zs25x846c/6682zt197/qf85q241d/ncit0524.pdf - [15] Solomon, A. et al. – “Composition of fig seeds” – Scientia Horticulturae, 2006

Unable to verify – exact article not found - [16] Vinson, J.A., Zubik, L., Bose, P., Samman, N., and Proch, J. – “Dried Fruits: Excellent in Vitro and in Vivo Antioxidants” – Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 2005 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15670984/

- [17] Aizen, M.A. and Harder, L.D. – “The Global Stock of Domesticated Honey Bees Is Growing Slower Than Agricultural Demand for Pollination” – Current Biology, 2009 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982209009828